A Sermon Preached at Saint John’s Cathedral, Denver on Easter Sunday 2014

In Eastern Christian traditions, it is customary, after Easter to greet people by saying, “Christos Anesti” to which the other person responds “Aleithos Anesti” – this greeting means “Christ is Risen” and the reply means, “He has risen indeed.” We opened mass this morning with the same salutation in English – The Lord is Risen – The Lord is Risen indeed.

In the west the custom is one that is restrained to these Easter liturgies. We enter this space and greet one another in the name of the Risen Lord.

In the East though, the greeting is one that is made on the streets, in coffee shops, at the barber, or in countless other places. Christians greet one another with Easter joy and that joy is made manifest, in that simple greeting, in their everyday relationships – all those they encounter are greeted with Resurrection joy and hope on the lips.

We have spent much of the last week meditating on the lessons of Christ’s betrayal, suffering, and death. We heard the story of Judas (who was the first person to leave Mass early). We heard of soldiers and crowns of thorns. We heard of a crowd’s cruel mockery and a Savior’s last breath. We waited and watched. We prayed and repented.

I have always had a bit of a bias – I have always been just a little more fond of Lent than I have been of Easter. The more penitential and garment-rending the better. The more dismal the hymns and self-abnegating the practices were the more I felt like it was really Church.

I think what I liked, if I can put it that way, about Lent was that it demanded something of us as Christians. We were called to examine our hearts and make some sort of sacrifice for our faith.

Yet, as this Easter has come around I am being drawn into its mysteries. I believe that there is something deeply demanding about Easter – it demands that we hope.

In this culture, in these economic times, in this age of international uncertainty, and in the face of increasing secularism – Easter asks something of us that no Lenten discipline can ever match – that we hope.

Imagine those apostles. That company that came in on Palm Sunday seeing their Messiah riding on in Majesty. Then, fast forward, the cross has been carried and the tomb shut. They must have been devastated, fighting with one another over what to do next, recriminations must have flown over who had stood by Jesus the longest, who was the greatest now that their Hosannas died on parched tongues.

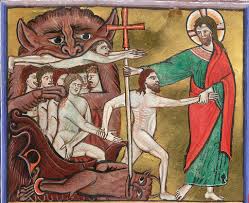

Into this scene comes the risen Christ. Into this scene comes hope.

In many churches, one Holy Week observance is to remember the seven last words of Christ – those phrases he says across the Gospels that are so often seared in our consciences.

“Father, forgive them.”

“You will be with me in paradise.”

“Behold your mother.”

“My God, why have you forsaken me?”

“I thirst.”

“Into your hands, O Lord, I commend my spirit.”

“It is finished.”

These words, at the center of the story of Christ’s Passion, are also at the heart of our Resurrection life.

The story of this past week is that we who might think ourselves distant from God are closer than we can ask or imagine – his love breaks the bonds of sin and death as we are forgiven, as forgiven as those Christ begs his Father to forgive – and we know the promise of paradise as surely as the thief crucified alongside Jesus.

We are drawn together, by Christ’s blood, into a new family who are heirs of his promise. God, no matter our desperation, anger, doubt, or anxiety has never forsaken us. He weeps with us, rejoices with us, and thirsts with us. At the heart of God’s mercy is our hope that we too can commend our spirit to him – that we too are God’s well-beloved sons and daughters.

We come here hoping it is true. We reach past loss or doubt fear and wonder if we can dare to believe.

Here, in the Gospel, Jesus returns before despair can define these men and women. Before they can become simply people of terrible loss they become something entirely new, people of hope.

Here, in the Gospel, Jesus returns before despair can define these men and women. Before they can become simply people of terrible loss they become something entirely new, people of hope.

This past week has reminded us that the Christian life is not one free of suffering, fear, and even pain. Even Jesus, in the garden says “take this cup from me” and on the cross “why have you forsaken me?” And yet Christ’s “It is finished” is both an end and a new beginning.

For even as his life was ending, God was setting into motion the final freedom from death – hope was born in a tomb as it had once been born in a manger.

Our challenge now is to live with Resurrection hope in such a way that we can help others know the promises of Christ. How can we live in such a way that those whom we meet can see hope enter their lives through ours?

Can we look into the eyes of one who has wronged us and say, “Father, forgive them.”

Can we see the woman huddled under a tree on a winter night, dressed in dirty hand-offs, and hear Jesus say, “Behold your mother.”

Can we hear the cry of those who thirst and those who think themselves forsaken and walk with them toward paradise’s promises?

In Christ’s last hours we saw the essence of Christian life stripped to its core and the shape of Resurrection life was revealed.

I have often dismissed the all-too-cheery phrase “Easter People” to describe Christians of a certain grinning, happy go lucky stripe. Yet if the phrase means a people who dare to hope, a people who have touched the wounds, a people who yearn to see Christ in one another, a people who forge ahead in the face of the many temptations to abandon hope – then we should be proud to be an Easter People.

The Resurrection is calling us, daring us, drawing us into that most challenging and demanding of disciplines – that of Easter hope.

May all those who meet you this Easter season know Easter hope through you – may your friends, co-workers, partners, children, parents – may all those you encounter hear and see and know in you that Christ is Risen indeed.