For those that are readers, this essay represents a small shift in the blog. I am going to endeavor over the next few posts to delve into some sources from our tradition, at some length, to explore core elements of our doctrinal and theological inheritance as Anglicans. I think one of the great challenges of the Church right now is that we have overlooked the importance of sound theology and it would be a good thing for there to be a few places where the riches of our tradition were being explored and mined for enduring truths.

This does mean that I will post with less frequency and probably with less intensity about the issues of the day – but I hope these next few posts (which will be somewhat longer) will provide some new avenues for discussion and engagement with our tradition.

One of the real shocks in the recent contretemps over Baptism and Communion was the paucity of much of the Eucharistic theology of the Church. The position papers that were put together by various dioceses and working groups were almost scandalous in their utter abandonment of anything that resembled the Eucharistic theology that we have inherited from both the Reformed and Catholic branches of the Church.

One of the chief oversights in much of the discussion was the nature of the Eucharistic sacrifice. I heard lots and lots of meal language, fellowship chatter, and radical welcome talk, but I heard perilously little about the nature of the Eucharist itself – that it has, at its heart, a sacrificial character that is participated in by those who receive. We take part both in the sacrifice and in being offered as one Body.

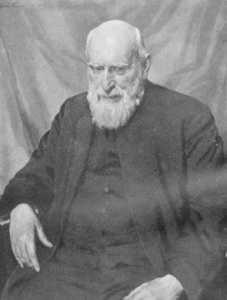

I remembered a solid book I read by Anglican theologian Darwell Stone called, “The Eucharistic Sacrifice.” It is actually a collection of sermons from 1919 that examine the nature of Christ’s sacrifice and our union with Christ in that self-offering.

I remembered a solid book I read by Anglican theologian Darwell Stone called, “The Eucharistic Sacrifice.” It is actually a collection of sermons from 1919 that examine the nature of Christ’s sacrifice and our union with Christ in that self-offering.

“The Eucharist is the presentation of the body and blood, the human life, of our Lord to God the Father by the Church. … The consecrated Sacrament is the body and blood of the Lord. He is present, and therefore we offer Him in sacrifice to the Father. Moreover this sacred presence explains the gift of God to ourselves. The Lord is in His Sacrament, and therefore He is not only offered in sacrifice to the Father, He is also in our Communion bestowed upon us. Thus, both for the sacrifice to the Father and for the gift to Christians there is need of the truth that at the consecration the bread and the wine are made to be the body and blood of Christ.”

Stone vigorously defends the Real Presence of Christ in the elements on the altar. The understanding of the Eucharist as sacrifice rests, for Stone, on Thomistic conceptions of matter, form, and their relation to the spiritual. Stone begins his work with an examination of sacrifice in Jewish, Pagan, and Christian traditions.

Stone states, “There are many resemblances between sacrificial ideas in the Old Testament and those in the New Testament, between those of pagans and those of early Christians.” However, those resemblances are mitigated by the nature of those sacrifices and their adequacy and efficacy over time and across humanity. Stone writes, “In sharp contrast [to Jewish writers] the Christian writers emphasize that the sacrifices of the Christian religion are spiritual. They are ‘spiritual sacrifices’ which St. Peter says that the Christian Church is to offer up.” The Christian offering and sacrifice was one that was not a carnal one but one of the spirit. All Christians are called to offer up this sacrifice. Christians, like the Jews, have a priestly caste “through whom the sacrificial functions of the society can be performed.” Christians and Jews, despite the difference in the nature of their respective sacrifices are unified by their election as “as sacrificial people with a special vocation from God which calls to sacrifice.”

There are marked similarities between the intent and exchange involved in Jewish sacrifice and the atonement offered through Christ’s sacrifice. In Jewish sacrifice, Stone identifies three fundamentals. He claims,

First, the sacrifice was a gift from man to God. As a gift, it was an acknowledgement of God’s power and supremacy, of the duty owed by the creature to the Creator. Secondly, it was a means of propitiation. The blood of the slain victim, itself the symbol of life, was offered to God as a means of pleading for the forgiveness of sins…Thirdly, the Jewish sacrifices were a means of communion between God and man.

Stone makes a swift transition to articulating the created kinship between God and man. Stone writes, “The truth, ‘God created man in His own image, in the image of God created He him,’ lies behind all that is possible of human intercourse with the divine.” Stone clearly makes the allusion between the Jewish sacrificial exchange and the Eucharist. For example, he writes, “In sacrifice the worshippers took part in a sacred meal which they were regarded as sharing with Almighty God Himself. In it there was access to God. In it the altar of sacrifice was also the table of the Lord. In it the food was the bread of God.” The sacrifice of Jews was “gift, propitiation, and communion.”

Sacrifice and the sacrificial teaching of the New Testament in particular is fulfilled in the sacrificial offering of Christ upon the cross for the atonement of the whole of humanity. Stone writes,

The sacrificial teaching of the New Testament reaches its height in the sacrifice of Christ Himself. Our Lord’s earthly life, His death, His resurrection, His ascension, His heavenly life, are seen to include the aspects of sacrifice gathered from the Old Testament, gift, propitiation, communion. In Him are the dedication to God of a perfect human life, the means of divine forgiveness for man, the means of communion between man and God. He describes Himself as a sacrifice on our behalf.

Christ is identified with a number of titles which indicate His sacrificial offering. He is acknowledged as Lamb of God which taketh away the sins of the world, passover, and propitiation for sins. Stone cites these and states, “In the Old Testament victim, the blood was the symbol of life, not of death. It was when the blood of the slain victim was poured out before God that the crucial moment in the propitiation was reached.” Christ, with His blood, redeemed humanity in the ultimate expression of human unity with god and forgiveness in God. Christ’s perfectly human blood “the symbol and essence of His whole human life” fulfilled the whole of the offering of atonement.

The vital element of the sacrifice of Christ was the surrender to God’s will. God’s universal salvific intent was manifested in the oblation of Christ. Christ’s suffering and death give meaning to sacrifice and suffering across the ages. Stone writes,

In the Lord Himself is the central sacrificial life of the universe. There have been pictures of it all the world over. The sufferings of the brute creation, the cries of women and children, the agonies of men, the dedication of will in life and in death, the rites, sometimes touching, sometimes repulsive, of heathen religions, in particular the ordered system of the Levitical law, all of these have in their different ways pointed on to the sacrifice of the cross, to the sacrifice presented in heaven; and in the light of Christ alone can their meaning ever be seen.

It is in this passage that Stone begins to make clear the link between the Incarnation and the physicality of Christ as perfect man and the sacrificial nature of the Eucharist. For the sacrifice of the Eucharist to make sense and for the suffering of the world to have meaning Christ must have lived and died as man. Stone states that the life of Christ is “the centre and strength of all Christian life and worship.” Stone declares, “As He is, so is the Church; as He is, so is the Christian; in His offering He offers those who are His.” The Church and the Christian find in Christ their anthropology and pattern. We observe the call to sacrifice and obedience to God. The fulfillment of life in God is represented as sacrifice. Stone states, “If we shall find that the Eucharist is the sacrifice of the Christian Church, we shall find a truth which is in harmony with the whole current of the Christian faith.”

The sacrifice of Christ points toward our unity with God. The harmony restored by the death and resurrection of Christ Jesus is indicated in other portions of the work of God and Christ. Stone claims that three aspects of God’s ongoing work indicate this divine-human unity. First is, “the distinctive character of man through creation whereby he possesses personality which enables him to be in communion with God.” Second, is the Incarnation in which “the relations between God and man obtain a new character” in which “there is a new use of that which is material.” Third, we have the Sacraments through which there is “actual union between Christians and our Lord’s incarnate life embodied in the life of His body.” All of these additionally point toward the work of the Holy Ghost. Stone writes, “Between His death and the life of the Church were his resurrection and ascension and the outpouring of the Holy Ghost.”

It is in the action of the Holy Ghost that Christians are brought into unity with Christ. We become members of the one body. Stone cites S. Paul in claiming “the Eucharistic gift is a participation in the body and the blood of Christ.” The bodies of individual Christians, by their baptism and commitment to new life, become a vehicle in “the economy of grace.” The Christian, by their unity with Christ in the Holy Ghost become filled with a potential for spiritual refreshment and reinvigoration in Him. They are made alike unto Christ, transitioning from suffering and humiliation to glory alike to the Lord Christ’s. Stone states, “It is through the operation of the Holy Ghost that in Baptism, the gate of all other Sacraments, our bodies are made the means through which we receive spiritual grace.”

The unity that often seems so elusive between our own soul and body, between the will of God and our own will, is brought about in the indwelling of the Holy Ghost and in our unity with Christ in the Sacraments. The life of prayerful obedience patterned in the life of Christ direct us toward new life and humble glory in and with Christ. Stone claims, “In our spiritual actions of faith and prayer we use our bodily brain as the instrument of spirit; in all kinds of actions which are instinct with spiritual purposes the spirit uses the body…” The body is the site of humiliation and sin and yet is the vehicle for grace and new glory. In Christ we see the pattern of shame and humiliation on the walk to Golgotha transformed into the redemptive might of the resurrection and ascension. As we partake in the divine nature of Christ, we make this journey from humiliation and dessication to glorification in the body and blood of Christ. Stone writes, “Christians actually receive the Holy Ghost , and through His operation are brought into actual union with the deity of Christ by means of His human nature, body, and soul.” It is in our Sacramental participation that we move ever toward unity in and with God. The Eucharist, however, is the apex of our Sacramental participation. Stone claims,

In the Eucharist the Holy Ghost acts by His divine power on the risen body of Christ in heaven and on the earthly elements which have been offered on the altar, and he transforms those elements into the body and blood of Christ. This divine action postulates the abiding existence of Christ’s human body; it assumes the spiritual state, unhampered by ordinary laws, of the body of Christ, through His resurrection and ascension; it utilizes that union of body and soul which makes it possible for each to be the servant of the other in spiritual life.

Our Sacramental life in Christ prepares us to live in unity with God and one another as we are called to a pattern of sacrificial and cruciform living. We are drawn ever nearer to God and to one another.

This process depends, in part, on our own intention with regard to receiving the body and blood of Christ. The body of Christ is given unto us when we make our communions. However, our own spiritual preparation in and with the Holy Ghost must be one which allows the body and blood to make their presence felt in and through us. Stone states, “our moral and spiritual benefit depends on the will with which we offer, the will with which we receive.” The sacrifice of Christ upon the cross and our unity in His body and blood are an example of how the evil and the good can co-dwell in an instant. The betrayal of Christ, his passion and crucifixion, are all transformed in glory. We too can be sites of vice or victory. Stone writes, “The Lord is there present to pardon and strengthen and bless. But to receive His blessing, our good will must go out to meet His.” The Eucharist challenges us to remember the ever-offered grace of God as well as the weight of the whole of man’s free will.

In Christ all other incomplete sacrifices and attempted propitiations have been made complete. Stone asserts, “From His supreme sacrifice Christian life and Christian worship derive their nature. The more they are like Him, the more are they full of sacrifice. The Eucharist is at the heart of Christian life, and is the climax of earthly worship.” In the Last Supper, the disciples who are with Jesus are given a foretaste of his sacrifice as each word he speaks is freighted with portent. Even in this meal, Stone states, “The things which He used in the new rite were to Jewish minds themselves sacrificial.” The scene in the Upper Room was loaded with sacrificial meaning and import. In fact, Stone claims, “The term, ‘poured out’ in the words ‘ this is My blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many unto remission of sins’ was the very phrase which described the climax in the sacrifice of the Jews.” The description of the food as Christ’s own body and blood by Christ is proof for Stone that “the consecrated Sacrament is the Lord Himself. That which is presented to the Father when the offering is made is the Lord’s body, the Lord’s blood, His very life.”

Our participation in a sacrificial offering is evidenced by our use of the terms priest and altar. For Stone, these usages are so integral to our conception of Christian worship that they hardly bear comment. He states, “They come to men’s minds naturally as the appropriate words; and when we are using appropriate language about anything, we do not spend much time in explaining it.” However Stone proceeds to cite numerous church fathers as evidence for his clear assertion that the Eucharist must be understood as sacrifice in order to have theological meaning. He concludes this section by simply stating, “The Eucharist then is the Church’s sacrifice. In it the Church presents to the Father as a sacrificial offering the life of the Lord. It is His Body, it is His Blood, it is Himself. As the offering of Him, it is the offering of all that He has, of all that He is, of all that He has been, of all that He ever can be.” Along with Christ, because of the gift of divine-human unity, we are also afforded the chance to offer ourselves, our souls, and our bodies and “thus taking our part in the great offering, we are enabled to pray for our own needs and the needs of all the Church. Into the great stream of the sacrifice we pour the joys and griefs and desires of mankind.”

Stone cites John Henry Newman offering the quote, “’There are little children there, and old men, and simple labourers, and students in seminaries, priests preparing for Mass, priests making their thanksgiving; there are innocent maidens, and there are penitent sinners; but out of these many minds rises one Eucharistic hymn, and the great Action is the measure and scope of it.’” Along with the body of the Lord, the Church, in unity with Christ, offers all of that which makes it human, all of that which is ennobled by the Incarnation and also that which is stained by straying free will. It offers its all to Him that was, is, and ever shall be. It sacrifices itself making its own offering which is an offering that is of a piece with the perfect offering of Christ through the work of the Trinity. Stone claims, “This then is the central thought of the Eucharistic sacrifice. In it the Church presents to God the father the merits of Christ, the life of Christ, the death of Christ, the resurrection of Christ, Christ Himself, in pleading for all manner of needs.”

The offering of Christ and our unity with Him in the Sacraments and especially in the Eucharist rely on Christ’s presence made manifest in the consecration. Stone, on pages 29-32 makes numerous references to Scripture which demonstrate with force and vigor that Christ is present upon the altar and that those who receive Him “drinketh judgment.” Coupled with the New Testament evidence we also have the word and witness of holy tradition. Stone says, of this tradition, “there is a great main stream of testimony concerning Eucharistic belief which, viewed in detail or viewed as a whole, is extraordinarily impressive.” Stone cites S. Athanasius who stated, “’But when the great and marvelous prayers are completed, then the bread becomes the body, and the cup the blood, of our Lord Jesus Christ.’” This simple formulation is at the heart of the witness of holy tradition.

That tradition is consonant with manifold aspects of Christian doctrine and faith. Stone states that S. Athanasius’s simple construction is in harmony with the Incarnation insofar as “the hidden presence of God made Man in the holy Sacrament is that abiding outcome of the Incarnation wherein we are to rest until the vision of His glory is unveiled.” The material are made vehicles for spiritual grace via the Incarnation. The life of Christ was “real and complete” but also miraculous. The Sacrament of the Eucharist, in the same way, takes that which is real and brings about a marvel. The Eucharistic presence reveals and is indicative of the operation of the Holy Ghost in the world. Stone states, “The Lord’s mortal human life from its first beginning in the Virgin’s womb to the close of its mortality on the cross was empowered by the Holy Ghost. That strength of the Holy Ghost in Him did not cease with His death but abides forevermore.”

Stone delves into historical and theological questions surround the Eucharist. He begins with a quick note on Archbishop Cranmer’s formulation of the real presence which Stone says “recognizes some great truths” while being “inadequate.” Stone goes on to discuss the theories of Zwingli, virtualism, and receptionism. Of Zwingli’s conception of the Eucharist, Stone writes, “Before consecration they are bread and wine; and after consecration they are nothing more. Nor are they the means of conveying any specific gift.” The Eucharistic gifts are merely signifiers of a greater purpose whose “excellence” rests upon perceived symbolism. Virtualism, Stone describes as meaning that those who receive the Sacrament receive the “virtue of Christ’s body, although the Sacrament is nothin more than bread and wine.” Finally, Receptionism, Stone states, is the notion that “though the consecrated bread and wine remain bread and wine and are nothing more, yet faithful communicants at the time of receiving the Sacrament receive also the body and blood of Christ.”

All of these has, according to Stone, some spiritual value for they focus the mind and heart of the communicant on the nature and work of Christ and fix the memory upon the Lord. However, Stone iterates that opinions such as those of Zwingli and of Cranmer “must be set aside if the central truth of the Eucharist is to be maintained.” Stone goes on to argue that there have always been, across Christendom, disagreements and conversations regarding the precise nature of various elements of the Eucharist. He cites disagreements over issues of agency in the celebration of the Mass, the precise moment of consecration, and the method of the presence of Christ in the Sacrament as examples of points upon which there is not universal agreement. However, these differences of explanation and interpretation…leave that central truth unimpaired.” Stone advises those who would get caught up in these sorts of discussions that “it is our wisdom to fix our thought chiefly on what I have called again and again the central truth, the fact of the real presence on the altar in the Sacrament of our Lord and God.”

From Stone’s central concern, that the Eucharist is sacrificial and that Christ is present in the Sacrament, he draws some practical and devotional conclusions. First, the Eucharist is the central act of Christian worship and life. Sundays and other high festivals should not pass without one receiving the Eucharist according to Stone. Stone argues that the Eucharist is “the chief moment of prayer, into which are gathered hopes and fears, yearnings and entreaties, intercessions for others, supplications for ourselves. It is the service of principal dignity.” Out of this service of prayer, hope and dignity, the believer ought seek to “live a Eucharistic life which ever looks back to the Communion last received and forward to that which is to come. From the altar they take with them the Lord Himself to be their Companion in pain and in delight, in effort and in rest, in the bright hours of youth, in the steadier glow of middle life, in the waiting of old age.” By degrees of divine presence, the divinity is unveiled to us. Therefore, it is “with special adoration we bow before Him when the consecration makes the earthly elements to be the veils of His being…” An especial reverence is to be reserved for the Eucharist when the Lord is present and the Sacrament should be “continuously reserved in church” for the benefit of the faithful.

In the Eucharist, we are to be ever joyful, according to Stone. This is for the simple fact that Christ has made man free. Stone states of the early Christian communities, “Christ had set Christians free; and the freedom included the power to conquer sin and live in holiness.” This freedom combined with the ongoing unity with God and Christ in the Eucharist were sources of profound celebration for early Christians and remain our gladsome inheritance. No matter the persecution, degradation, or failings of Christians, we know that we have a unity with Christ in the Sacrament that cannot be shattered.

Robert+