Christmas at our house was always met with lots of joy mingled with a little bit of fear. You see, whenever we had some big event coming up like a camping trip, a vacation, or a weekend away, there would come the inevitable moment when my mother, overwhelmed with preparations (and our apparent lack of concern about those preparations), would suddenly declare, “Let’s just cancel it!”

So as Christmas lights needed to be hung, cookies needed to be baked, guest rooms prepared, travelers picked up, the house cleaned, the Christmas china found – as things got hectic and details seemed overwhelming, we always feared that we would hear that dreaded phrase, “Let’s just cancel it!” I remain convinced to this day that if any mortal might, with a word, cancel Christmas, it is my mother!

She always wanted us to have the perfect Christmas. And we all do this to some degree or another. We try to recreate that perfect memory, moment, or meal when Christmas day was just as it should be.

Yet, I wonder, if that first Christmas was just as Mary would have had it? Was that her perfect Christmas? Here she was, traveling at the government’s command, finding no room for shelter, giving birth amidst barnyard animals. This may not have been her perfect Christmas – but it is ours.

Thankfully, the perfect Christmas has already been had. That first night of Jesus’ birth was our perfect Christmas. God, at work in the meanest of circumstances, created a holy night which made possible our own new birth.

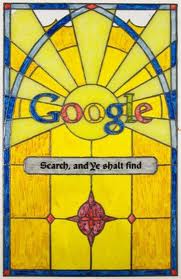

Too often we let the perfect get in the way of the joys of the moment. In our search for something just beyond our reach we fail to grasp the raw beauty of just what we have been given. Lying beneath the surface of what we see often lie true gifts of love, beauty, and grace.

A number of years ago, I was given a small box for Christmas. As I opened the box I saw a tarnished, dented, and rather well worn coin. It was an 1891 silver dollar coin. At first I was rather underwhelmed with this gift. I had hoped for an x-box or even a new book (when I was a child I was particularly fond of the Guinness Book of World Records or perhaps some new tome of Arthurian legends). Yet I had gotten a coin – and not even one I could use in a Coke machine.

Then my father began to talk about this coin. It had been in my great-grandfather’s pockets as a good luck charm in the trenches of World War I. It had been in my grand-father’s pocket in World War II. It had been in my father’s pocket as a good luck token since he was young. That coin, with all its dents and tarnish, told a story that no book could capture.

It was not its shine that made it beautiful but its tarnish.

My wife, a couple of years ago, received a spoon for Christmas. It was a red cooking spoon. It was rather a mess. Melted in places, a little bent, and discolored from use. She, unlike me, was overwhelmed with the gift – or perhaps as a Southerner she was just better at being graceful about odd presents than I was.

I tend to think not though, because this had been her grandmother and grandfather’s cooking spoon. It had served black-eyed peas on New Year’s Day, banana pudding at Christmas, and sweet potato casserole at Thanksgiving. Year after year it had been used at her family’s most cherished times together.

It was not its newness or shine that made it cherished but its years of use and the love it conveyed.

Beneath every seemingly less than perfect moment and gift is more. More of life, more of love, more of God’s many gifts to us. How often do we let the search for the perfect overshadow all that we are given?

The wonder of Christmas, of Christ’s coming, is that it was done in such a very human and raw way – filled with excitement and exhaustion. Beneath dirt and dust, fear and trembling, cold and night lay joy, hope, and promise.

Less than perfect circumstances revealed a perfect love.

It is the essence, the heart of things, that makes them perfect rather than our efforts to make them so. Whether a coin, a spoon, or a holiday – there is a heart in them all that makes them more – and for that we give thanks.

Our struggle is to remain ever mindful of our blessings despite living in a culture that sells us celluloid visions of perfect days, precious moments, toned selves, and richer futures if we just have more – if we were just more.

A Christian view of the world is one that sees the movement of the divine all about us, not in what we could have if we just worked harder, but in all that we have, in all of the gifts, people, and moments we have been given.

An art historian, looking a painting, sees the brushstrokes, use of color, symmetry, and perspective and knows that this is the work of Rembrandt. A trained musician listens to the chords, notes, and form of a piece and hears Beethoven.

Faith is both art and discipline because it is no easy or precise task to hear the voice of the Holy One – to receive the one whose own received him not – and it takes practice, a lifetime of practice, to know the God who knows us.

Christmas reminds us that God is not a deity of serene detachment, content to create the cosmos, and then stand aside as it grinds along to its natural ends. Creation is not God’s hobby. This is a Father whose passionate Love is offered for us, for me, and for you – whose whole being is drawn to dwell with us. This is a God whose first dwelling here was a creche, whose sign a cross, and who promises to be with us always. In the face of such love, all we can do is give thanks.

Tonight we sang “Once in Royal David’s City.” As it began, we strained a bit to hear that voice begins the story, “Once in royal David’s city stood a lowly cattle shed…” It echoes around us and then we realize that, from some place deeper than memory, we know the tune.

New voices join in, accompanied by the lush sound of the organ. We hear a bit more, “He came down to earth from heaven…”

All around us people move, smoke comes forth, and we sing. Before we even know it, we are singing loudly, some smiling, some with tears in their eyes as we hear the voices of those gone before us singing too, and with one loud voice we know and sing “our eyes at last shall see him, through his own redeeming love.”

The song swells and we sing not of an old story, something of the past alone, but of a promise that still echoes across the ages and resounds deep in our chest, “And He leads His children on, to the place where He is gone.”

We are constantly, throughout our short days, being asked to join in God’s song of redeeming love and to give thanks as we listen for the one who is Love in voices all around us.

We experience God’s love in the imperfect people and world around us. In being given a second chance by someone we have hurt. In the self-less love we receive from our friends, parents, children, partners and even our pets. In the gracious beauty of the liturgy here tonight.

The Christmas story, this perfect story, reminds us that it is through very real, rarely noble, and sometimes challenging people and experiences that we come to know the love of God – and we give thanks for that.

May this Christmas reveal more and more of God’s transforming love. May we see the gifts of God all about us in simple moments, loving friends, and even in odd gifts given and received. May we see signs of a God who takes all things (those new and those well-worn, those still shining and those tarnished by age), all people, and all our lives and ever holds them in perfect Love.

Robert+