Grab a cup of coffee and a lovely pastry, this one is a little on the longish side…

One of the facts of being Anglicans is that we are blessed to be part of a tradition formed and informed by both the Reformed, Evangelical stream of Christianity as well as the Catholic. We blend, in a unique way, traits of both that form a distinct persona within the spectrum of Christian belief, practice, and history.

Another fact is that we are part of a tradition within which is a distinct distrust of the perceived excesses of both strains. How many times have we heard that something is “too Catholic” or “too Evangelical” to be Episcopalian? We have many within our Church who have been hurt by the unreflective and reflexive adherence to respective sources of authority within both Protestantism and Roman Catholicism.

The genuinely sad thing is that we seem to often miss out on the gifts of both traditions in our rush to run from popular excesses in either. So we are left with a certain blandness that conveys, at its most unfortunate, uncertainty about Salvation, indeterminacy of Doctrine, and a lack of force in the proclamation of the Good News.

The Episcopal Church, I think, might be better served by finding within the scope of our tradition the best of both the Catholic and Reformed traditions rather than simply looking to other expressions of those traditions and saying, “Well, we’re not that!” It is easy, and sometimes emotionally gratifying, but ultimately unproductive to build an identity on correcting the negatives of other traditions.

The more difficult task is not differentiation but self-expression – who is it that we are not in reaction to the hurts of the past but in response to our hope for the future? Where are we being called as a people who come not cast out of one place but called into another?

When I came to the Episcopal Church it was with the great hope that I had found a place of Catholic Evangelism – or Evangelical Catholicism. It is a place that draws on what is essential to the nature of both Evangelicalism and Catholicism and holds these in tension – correcting the imbalances that arise and drawing strength and hope from the wellspring that is both.

Each tradition is a source of renewal and grace for both the individual believer and the whole Church.

When I think on our most essential quality, I often ponder the collect for Richard Hooker. It reads,

“O God of truth and peace, who raised up your servant Richard Hooker in a day of bitter controversy to defend with sound reasoning and great charity the catholic and reformed religion: Grant that we may maintain that middle way, not as a compromise for the sake of peace, but as a comprehension for the sake of truth; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever.”

The way forward for the Episcopal Church – and perhaps for the Church Universal – is not found in compromise for the sake of avoiding hard questions but in a comprehensive approach to our faith that draws from the wisdom of men and women across the ages who knew something more, something deeper, something true of the walk with Christ. This has happened in places and ways we can scarce imagine and continues to give new life in ways beyond our knowledge yet deep within our soul.

The great Evangelical truth is that Christ is at work in the life of each and every person and this is occurring within a world that the Catholic faith knows as full of promise and Presence. From the source of Scripture comes the knowledge of the grace offered in the Sacraments as we are made free by authority that comes from outside of ourselves.

What can a renewed Catholic Evangelism look like for the Episcopal Church?

At its core it should have at least the following:

A Belief that Christ is active in the Sacraments: Christ is at work in Baptism, Communion, Confession, and more. He is not at work simply with the goal of a vague amendment of life but for the sake of every person who would rest their hope in him – and beyond. He is at work in the Sacraments for the salvation of the whole of humanity – for the reconciliation of humanity to God that is mirrored in our reconciliation with one another. The Sacraments do not exist for their own sake (for the sake of the Sacraments) but for ours – to draw us more deeply as the People of God into the Holiness that is Christ’s own Body. The whole of the Church is taken up into the mystery of faith – and even as all are drawn so is each one – and as each is drawn so are we all. Participation in this mystery is not a right but a gift we should enter with thought, care, and preparation.

A Commitment to the Historic Church: There can be few deeper marks of hubris or heresy than to believe that the Holy Spirit is speaking to us and not to others. Across our history, the Holy Spirit has moved and given of himself to bring consolation and transformation. The very nature of our being is revealed in our forebears and their engagement with the Spirit. We inherit both the things that are of the Spirit of God and those that are of the spirits of this world, however. Thus, we are tasked with the work of discernment. Yet, we impoverish our whole self if we allow ourselves to cast aside aspects of our heritage without the careful witness of the whole Body of the faithful across time and boundaries. The Spirit moves across the ages and we receive this as the Holy Tradition of the Church. The Historic Church, the Church in her fullness, has lessons for each and every believer. Whether zeal, penitence, prayerful centering, selfless service, divine liturgy, theological inquiry, prophetic witness, scriptural rigor, and much more – across the whole of the Church’s being and history are lessons for us to deepen our participation in the ongoing revelation of the Holy One.

A Conviction that the Holy Spirit is still transforming us: A Spirit active across the ages is still speaking and proclaiming today – still drawing us into the wonder of God Incarnate. Just as we impoverish our identity by ignoring the past we do as much harm if we pretend that revelation is no longer being made known – that we have no more tidings to hear. We are being called by prophetic voices all around us to engage the world and to know its pain so that we may bring word of Christ the Healer. Just as we ask for the Holy Spirit to descend up Bread and Wine and to sanctify water, we need to be praying for the Holy Spirit to descend upon the whole of the Church and upon each of us daily that we might know and share the gifts of the Spirit.

A Belief that Sin, Powers, and Principalities are real: It is an unfortunate side-effect of having so many of us fleeing traditions that belabor the power of sin and death that we often now downplay their very real role in our lives. If we are, indeed, saved, then from what are we being saved? A simple answer would be, from ourselves. We are being drawn out of the depredations of unmoored souls adrift from the abiding strength of Christ. We spend much of our lives in the pursuit of some identity or another that will allow us to know ourselves as “independent” or “in control” and at the heart of our yearning for control or independence is a sinful impulse to know ourselves as belonging to ourselves. Only when we know ourselves as held in the hands of a Sustaining Father, shaped by the will of a Creating Christ, and caught up in the power of a Redeeming Spirit, can we begin to more clearly see the hold of sin and death. Often, those brought up in dysfunctional families are unable to see the dysfunction until they stand outside of the system and see the hold it had over their energy and being. In the same way, we need the community and the Church to help us stand outside of the shape and structure of society and help us name that which is sinful and holding some piece of us in its grip. The Church gives us the vocabulary to name that which must be exorcised in our individual and corporate lives and to name and hold onto that which is holy and life-giving.

A Belief that a relationship with Christ matters and is decisive for individuals and the whole Church: A world of diversity makes the declaration of the Lordship of Christ a sometimes uncomfortable proposition. We encounter good and even holy men and women of different and sometimes no faith and ask ourselves how a universal truth claim might be made. Yet, the way forward is not with bland or generic attempts to erase difference but to engage difference with the holy awareness that we just might be wrong. And yet, we know that our own lives and the lives of those we know, have been bought with the Love of Christ. That conviction and conversion gives us a certain foolishness to offer Good News. The most fruitful conversations I have ever had about difference were not attempts to erase or erode difference but to name it and share stories of where that difference had played out in our lives. A conversation with another is not a chance to convert them (though the Spirit may just lead that change of heart) but a chance to know our faith deepened by encountering the diversity of God’s Creation. We lead not with the fear that another person might be damned but with the joy that we are known and claimed as Christ’s own. No one is saved as an individual alone and no Church is truly holy without a Holy People of God who know themselves, in their deepest self, as given new life.

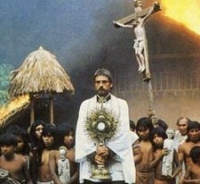

A Conviction that sharing the Good News is required for those transformed by the Good News: A people given Good News are called to share the Word with others. Sharing the Good News is the stuff of reaching the people of God in the way that God reaches us – with tenderness, compassion, forgiveness, and love (though this may mean bearing hard truth). In the way that Jesus walked amongst us and gave of himself we are called to be among those for whom Christ gave himself. We are to walk with the living Word – devote ourselves to be walking Sacraments – bearing witness to the Presence of Christ among us. The reality of God with Us is made known in our own willingness to be with, among, and alongside. Each of us is given a bit of the Good News to share in all the ways we know – with each of our many gifts we are called to offer some glimpse of the one whose very nature is relationship and self-giving. This is at the heart of good stewardship – that God blesses and we share that blessing to bring others word of God’s abundance. At the heart of Good News is God’s great abundance – the outpouring of God’s own self.

A Conviction that sharing the Good News is required for those transformed by the Good News: A people given Good News are called to share the Word with others. Sharing the Good News is the stuff of reaching the people of God in the way that God reaches us – with tenderness, compassion, forgiveness, and love (though this may mean bearing hard truth). In the way that Jesus walked amongst us and gave of himself we are called to be among those for whom Christ gave himself. We are to walk with the living Word – devote ourselves to be walking Sacraments – bearing witness to the Presence of Christ among us. The reality of God with Us is made known in our own willingness to be with, among, and alongside. Each of us is given a bit of the Good News to share in all the ways we know – with each of our many gifts we are called to offer some glimpse of the one whose very nature is relationship and self-giving. This is at the heart of good stewardship – that God blesses and we share that blessing to bring others word of God’s abundance. At the heart of Good News is God’s great abundance – the outpouring of God’s own self.

A Grounding in Scripture that welcomes the Word of God into our daily lives: A people who read, mark, and inwardly digest the word of God will be marked by that word. There is something life-giving and powerful in the engagement with the deepest stories of our faith. In the same way that we can appreciate the complexity of a dish when we’ve delved into a cookbook or two, the complexity, joy, and demands of our faith take on a new depth each time we open God’s word and let ourselves be transformed by it. Of course, this means we will wrestle with hard passages, frustrating bits, and confusing narratives. We will stumble over names, dates, and places. We will be told things we might not want to hear and delight to discover things we didn’t dream were written for us. Reading the Bible is like being told stories of your family tree – sometimes shocking, sometimes a little boring, sometimes liberating, always telling us a little more about who we are and where we come from. God’s holy word, passed on to us through the work of the Holy Spirit (and no small amount of Byzantine maneuvering), is given to us as guide and gift to be the place where we begin to know the story of God’s unfolding work, the nature of Christ, and the birth of the Church. We will be unsettled and convicted – and welcomed in new ways into the story of Salvation.

A Pattern of Prayer that shapes our days: Paired with a daily pattern of Scripture reading is a daily practice of prayer and marks and shapes our daily life. A Church prays. Period. If we are to be the Church outside the walls of our buildings then we have to pray. Period. We are given a pattern for this in the Daily Office. A young nun was once walking through the halls of the nunnery away from the chapel, a much older nun saw her in the hallway and asked, “Sister, are you not going to prayers?” The younger nun replied, “I just don’t feel like it today.” The older nun, sighed and smiled and told her, “Sister, I have not felt like going to prayers for 20 years – which is why I go.” And off they went. The purpose of a regular pattern of prayer is not our enjoyment – it is a way of structuring our day with God’s will for us in mind. We hear a bit of Scripture and remember the One who guides our days. This will not always be an unadulterated joy or moment of bliss – prayer (like life) is often a thing of offering and struggle which is punctuated by moments of clarity, understanding, and joy. Like so many things, without the investment of ourselves in regular patterns of spiritual discipline, it becomes harder and harder for us to hear the Holy Spirit speaking in, through, and to our days. One of the things about a regular pattern of prayer is to hear God’s charge to us in the morning (to serve God without fear, in holiness and righteousness as we go before the face of the Lord). We close our day of work hearing the promise of God (He that is mighty has done great things for us and fills the hungry with good things). We go to bed with Compline (Into your hands O Lord I commend my spirit). Prayer brackets our days and prepares us to hear, serve, and trust more fully.

A Sense of the Power and Promise of Worship: Whether in the joyful strains of a full Gospel choir, the rich hymnody of Choral Matins, the simplicity of an 8:00am Low Mass, or the choreography of Solemn High Mass, there must be a sense that worship is an act of profound and holy joy. We are given injunction, over and over again, to praise God with our whole selves. With all of our being we lavish upon God our share of Mary Magdalene’s fragrant oil. We offer from the bounty of God the sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving. This is a necessarily Evangelical and Catholic act – it engages the whole person and deepens their encounter with the Holy One who makes himself known to us as the blessed company of all believers. If we want people to think something important is happening at church then we need to act as if something is. In a world of hyper-marketing there is nothing more winning and latent with potential than true, unvarnished honesty. The power of lovingly and attentively offered worship is that we can give others a glimpse not only of the majesty of the one we worship but a sense of just how we are being caught up in the Wonder that is his Presence among us.

There is Holy Mystery: In the unanswered questions of our faith, in the divine-human interplay of the Incarnation, Crucifixion, Resurrection, and of Baptism and the Mass – in all of this and in countless other ways there is Holy Mystery at work in our faith. Our attempts to explain the Sacraments or explain the nature of Salvation are ultimately the grasping attempts of creatures to ascribe motive to the Creator. We know the story of faith and we grasp for its deeper meanings in the eddies and currents we feel washing about us. Beyond the order of expectations and the patterns of explanation is the salient fact of our faith – we see through a glass dimly. We are left with the one great mystery which we explore together in Word and Sacrament, by fits and starts, as individual believers and the whole Body. We offer together the lasting Good News and the joyful proclamation – Christ has died, Christ is Risen, Christ will come again.

These are not the only marks of Catholic Evangelism or Evangelical Catholicism, yet they are a beginning such that we can find anew the particular vocation of the Episcopal Church and deepen our shared life and labor as we work, pray, and give for the spread of the Kingdom.

Robert

This Body itself is not outwardly visible – it needs outward signs to be known to the world. It is our willingness to show forth in our lives what we proclaim with our lips that shows what it means to be the Church. In a time when fewer and fewer people will read Scripture growing up or receive the Sacraments as part of their everyday life – it is that much more vital that we offer some way for them to see and know something of the simple kindness and love of Christ.

This Body itself is not outwardly visible – it needs outward signs to be known to the world. It is our willingness to show forth in our lives what we proclaim with our lips that shows what it means to be the Church. In a time when fewer and fewer people will read Scripture growing up or receive the Sacraments as part of their everyday life – it is that much more vital that we offer some way for them to see and know something of the simple kindness and love of Christ.